Stringing Along with DAX: Dive Deep into Text Expressions

Ever felt like your data was whispering secrets just beyond your grasp? Dive into the world of DAX Text Functions and turn those whispers into powerful narratives. Unlock stories hidden within text strings, and let your data weave tales previously untold.

Introduction to DAX Text Functions

We live in a world that’s overflowing with data. But let’s remember: data can be so much more than just numbers on a spreadsheet. It can be the letters we string together, and the words we read. Get ready to explore the exciting world of DAX Text Functions!

If you have ever worked with Power BI, you are likely familiar with DAX or Data Analysis Expressions. If you are new to Power BI and DAX check out these blog posts to get started:

Power BI Row Context: Understanding the Power of Context in Calculations

Row Context — What it is, When is it available, and its Implications

Power BI Iterators: Unleashing the Power of Iteration in Power BI Calculations

Iterator Functions — What they are and What they do

From Data to Insights: Maximizing Power BI’s Calculated Measures and Columns for Deeper Analysis

Are you ready to take your data analysis to the next level?

DAX is the backbone that brings structure and meaning to the data we work with in Power BI. Especially when we are dealing with textual data, DAX stands out with its comprehensive set of functions dedicated just for this purpose.

So whether you’re an experienced data analyst or a beginner just starting your journey, you have landed on the right page. Prepare to explore the depth and breadth of DAX Text Functions. This is going to be a deep dive covering various functions, their syntax, and plenty of of examples!

For those of you eager to start experimenting there is a Power BI report loaded with the sample data used in this post ready for you. So don’t just read, dive in and get hands-on with DAX Functions in Power BI. Check out it here:

GitHub – Power BI DAX Function Series: Mastering Data Analysis

This dynamic repository is the perfect place to enhance your learning journey.

LEFT, RIGHT, & MID — The Text Extractors

Starting with the basics, LEFT, RIGHT, and MID. Their primary role is to provide tools for selectively snipping portions of text, enabling focused data extraction. Let’s go a little deeper and explore their nuances.

LEFT Function: As the name subtly suggests, the LEFT function fetches a specific number of characters from the start, or leftmost part, of a given text string.

The syntax is as simple as:

LEFT(text, number_of_characters)

Here, text is the text string containing the characters you want to extract, and number_of_characters is an optional parameter that indicates the number of characters you want to extract. It defaults to a value of 1 if a value is not provided.

For more details see:

Learn more about: LEFT

RIGHT Function: The RIGHT function, mirrors the functionality of LEFT and aims to extract the characters from the end of a string, or the rightmost part.

The syntax is the same as we saw for LEFT:

RIGHT(text, number_of_characters)

Learn more about: RIGHT

MID Function: Now we have the MID function. This is the bridge between LEFT and RIGHT that doesn’t restrict you to the start or end of the text string of interest. MID enables you to pinpoint a starting position and then extract a specific number of characters from there.

The syntax is as follows:

MID(text, start_number, number_of_characters)

Here, text is the text string containing the characters you want to extract, start_number is the position of the first character you want to extract (positions in the string start at 1), and number_of_characters is the number of characters you want to extract.

For more details see:

Learn more about: MID

Practical Examples: Diving Deeper with the Text Extractors

Let’s dive deeper with some examples. Let’s say we have a Product Code column within our Product Table. The Product Code takes the form of product_abbreviation-product_num-color_code for example, SM-5933-BK.

We will first extract the first two characters using LEFT, these represent the product abbreviation. We can create a calculated column in the products table using the following expression:

Product Abbrev = LEFT(Products[Product Code], 2)

Next, let’s use RIGHT to extract the last two characters which represent the color code of the product. We will add another calculated column to the products table using the following:

Product Color = RIGHT(Products[Product Code], 2)

Lastly, to pinpoint the unique product number which is nestled in the middle we will use MID. We add another calculated column to the products table using this expression:

Product Number = MID(Products[Product Code], 4, 4)

Together, these three functions form the cornerstone of text extraction. However, they can sometimes stumble when there are unexpected text patterns. Take, for instance, the last row shown below for Product Code TBL-57148-BLK.

You might have noticed that the example expressions above may not always extract the intended values due to their reliance on hardcoded positions and number of characters. This highlights the importance of flexible and dynamic text extraction methods.

Enter FIND and SEARCH! As we venture further into this post, we will uncover how these functions can provide much-needed flexibility to our extractions, making them adaptable to varying text lengths and structures. So, while the trio of LEFT, RIGHT, and MID are foundational, there is a broader horizon of DAX Text Functions to explore.

So, don’t halt your DAX journey here; continue reading and discover the expanded universe of text manipulation tools. Dive in, and let’s continue to elevate your DAX skills.

FIND & SEARCH — Navigators of the Text Terrain

In the landscape of DAX Text Functions, FIND and SEARCH stand out as exceptional navigators, aiding you in locating a substring within another text string. Yet, despite their apparent similarities, they come with clear distinctions that could greatly impact your results.

FIND Function: the detail-oriented one of the two functions. It is precise, and is case-sensitive. So, when using FIND, ensure you embrace the details and match the exact case of the text string you are seeking.

The syntax of FIND is:

FIND(find_text, within_text[, [start_number][, NotFoundValue]])

Here, find_text is the text string you are seeking, you can use empty double quotes "" to match the first character of within_text. Speaking of, within_text is the text string containing the text you want to find.

The other parameters are optional, start_number is the position in within_text to start the seeking and defaults to 1 meaning the start of within_text. Lastly, NotFoundValue although optional is highly recommended and represents the value the function will use when find_text is not found in within_text, typical values include 0, -1.

Note: if NotFoundValue is not specified and is not found in the function will return and error.

For more details see:

Learn more about: FIND

SEARCH Function: SEARCH is the more laid-back of the two functions. It is adaptable and does not account for case, whether it’s upper case, lower case or a mix SEARCH will find the text you are looking for.

The syntax for SEARCH is as follows:

SEARCH(find_text, within_text[, [start_number][, NotFoundValue]])

SEARCH operates using the same parameters as FIND, which can facilitate a streamlined approach when having to switch between them.

For more details see:

Learn more about: SEARCH

Practical Examples: Amplifying Flexibility

When combined with LEFT, RIGHT, or MID the potential of FIND and SEARCH multiplies, allowing for dynamic text extraction. Let’s consider the problematic Product Code TBL-57148-BLK again.

We started by extracting the product abbreviation with the following expression:

Product Abbrev = LEFT(Products[Product Code], 2)

This works well when all the product codes start with a two-letter abbreviation. But what if they don’t? The fixed number of characters to extract might yield undesirable results. Let’s use FIND to add some much-needed flexibility to this expression.

We know that the product abbreviation is all the characters before the first hyphen. To determine the position of the the first hyphen we can use:

First Hyphen = FIND("-", Products[Product Code])

For TBL-57148-BLK this will return a value of 4. We can then use this position to update our expression to dynamically extract the product abbreviation.

Product Abbrev Dynamic =

LEFT(

Products[Product Code],

FIND("-", Products[Product Code]) - 1

)

Next, let’s add some adaptability to our Product Color expression to handle when the color code may contain more than two characters. We started with the following expression:

Product Color = RIGHT(Products[Product Code], 2)

This expression assumes that all product color codes are consistently placed at the end and always two characters. However, if there are variations in the length (e.g. TBL-57148-BLK) this method might not be foolproof. To introduce some adaptability, let’s utilize SEARCH.

To determine the position of the last hyphen, since the color code will always be all the characters following this we can use:

Last Hyphen =

SEARCH (

"-",

Products[Product Code],

FIND ( "-", Products[Product Code] ) + 1

)

Here, for the start_number we use the same FIND expression that we did to locate the first hyphen and then add 1 to the position to start the search for the second.

With this position, we can update our Product Color function to account for potential variations:

Product Color Dynamic =

VAR _firstHyphenPosition =

FIND (

"-",

Products[Product Code]

)

VAR _lastHyphenPosition =

SEARCH (

"-",

Products[Product Code],

_firstHyphenPosition + 1

)

RETURN

RIGHT (

Products[Product Code],

LEN ( Products[Product Code] ) - _lastHyphenPosition

)

The updated calculated column finds the position of the first hyphen, and then uses this position to search for the position of the last hyphen. Once we know the position, we can use this position and the length of the string to determine the number of characters needed to extract the color code ( LEN(Products[Product Code]) - _lastHyphenPosition).

Through the use of FIND, SEARCH, and RIGHT, the DAX text extraction becomes more adaptable, and handles even unexpected product code formats with ease.

Similarly, we can update the the Product Number expression to:

Product Number Dynamic =

VAR _firstHyphenPosition =

FIND (

"-",

Products[Product Code]

)

VAR _lastHyphenPosition =

SEARCH (

"-",

Products[Product Code],

_firstHyphenPosition + 1

)

VAR _productNumberLength = _lastHyphenPosition - _firstHyphenPosition - 1

RETURN

MID (

Products[Product Code],

_firstHyphenPosition + 1,

_productNumberLength

)

Through these examples we have highlighted how to build upon the basics of LEFT, RIGHT, and MID by amplifying their flexibility through the use of FIND and SEARCH.

Practical Examples: Demonstrating Distinct Characteristics

When it comes to locating specific strings within a text string, both FIND and SEARCH offer a helping hand. But, as is often the case with DAX, the devil is in the details. While they seem quite similar at a glance, a deeper exploration uncovers unique traits that set them apart. What’s main difference? Case sensitivity.

Let’s explore this by comparing the results of the following expressions:

Position with FIND = FIND("rd", Products[Product Code], 1, -1)

Position with SEARCH = SEARCH("rd", Products[Product Code], -1)

In these example DAX formulas we can see the key difference between FIND and SEARCH. Both calculated columns are looking for “rd” within the Product Code. However, for SM-7818-RD we see FIND does not identify “rd” as a match whereas SEARCH does identify “rd” as a match starting at position 9.

Both of these functions are essential tools in your DAX toolbox, your choice between them will hinge on whether case sensitivity is a factor in your data analysis needs.

By mastering the combination of these text functions, you not only enhance text extraction but also pave the way to advanced text processing with DAX. The intricate synergy of FIND and SEARCH with other functions like LEFT, RIGHT, and MID showcases DAX’s textual data processing potential. Keep reading, as we journey further into more complex and fascinating DAX functions!

CONCATENATE & COMBINEVALUES — Craftsmen of Cohesion

While both CONCATENATE and COMBINEVALUES serve the primary purpose of stringing texts together, they achieve this with unique characteristics. CONCATENATE is the timeless classic, merging two strings with ease, while COMBINEVALUES adds modern finesse by introducing delimiters.

CONCATENATE Function: is designed to merge two text strings, with a syntax as simple as the concept.

CONCATENATE(text1, text2)

The first text string you want to merge is represented by text1, and the second text string to be merged is represented by text2. The text strings can include text, numbers, or you can use a column references.

For more details see:

CONCATENATE function (DAX) – DAX

Learn more about: CONCATENATE

COMBINEVALUES Function: combines text strings while also integrating a specified delimiter between them, adding some versatility when needed. The syntax is as follows:

COMBINEVALUES(delimiter, expression, expression[, expression]...)

The character or set of characters you wish to use as a separator is denoted by delimiter. The expression parameters are the DAX expressions whose value will be joined into the single string.

For more details see:

COMBINEVALUES function (DAX) – DAX

Learn more about: COMBINEVALUES

Practical Examples: Illuminating Their Craft

Let’s put these functions to use and examine some real-world scenarios.

Let’s say we need to create a new Product Label column in the Products table. The label should consist of the product abbreviation directly followed by the product number. We can achieve this using the previously created columns Product Abbrev Dynamic and Product Number Dynamic along with CONCATENATE. The expression for the new column would look like this:

Product Label =

CONCATENATE (

Products[Product Abbrev Dynamic],

Products[Product Number Dynamic]

)

The expression merges the dynamically determined product abbreviation and product number.

Now, let’s change it up a bit and work with creating a new measure with COMBINEVALUES. Say, we need a page of the report specific to the current year’s sales and we want to create a page title that provides the current year and the YTD sales value. Additionally, we want to avoid hardcoding the current year value and the YTD sales figure because these will continually change and would require continual updating. We can use COMBINEVALUES to meet this requirement, and the expression would look like this:

Yearly Page Title =

COMBINEVALUES (

" ",

YEAR (TODAY ()),

"- Year to date sales:",

FORMAT ([YTD Sales TOTALYTD], "Currency")

)

This measure, dynamically generates the title text by combining the current year (Year(TODAY())), the text string “- Year to date sales:”, followed by a YTD measure ([YTD Sales TOTALYTD]).

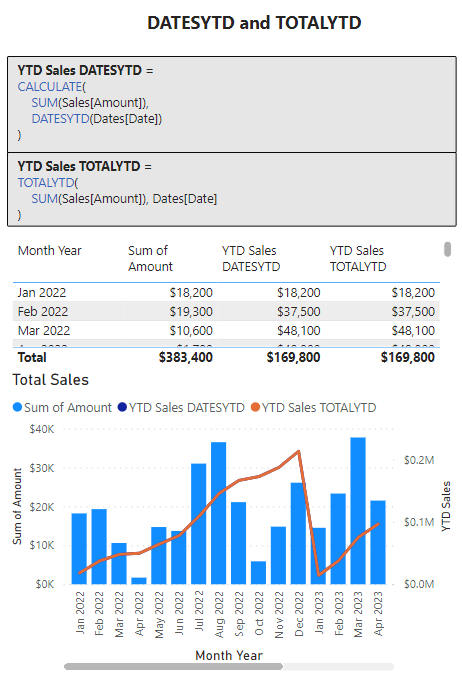

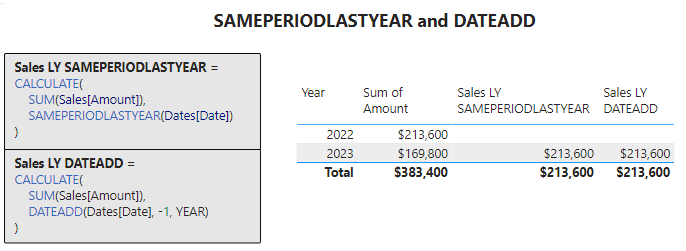

The [YTD Sales TOTALYTD] measure uses a another set of powerful DAX functions: Time Intelligence functions. For details on the creation of the [YTD Sales TOTALYTD] along with other Time Intelligence functions check out this post that provides an in-depth guide to these functions.

Time Travel in Power BI: Mastering Time Intelligence Functions

Journey through the Past, Present, and Future of Your Data with Time Intelligence Functions.

By mastering CONCATENATE and COMBINEVALUES, you can craft meaningful text combinations that suit various data modeling needs. Whether you are creating measures for reports or calculated column for your tables, you will find numerous applications for these DAX text function.

As we journey deeper into the realm of DAX, remember that the right tool hinges on your specific needs. While CONCATENATE and COMBINEVALUES both join texts, their nuanced differences could significantly influence the presentation of your data. Choose wisely!

REPLACE & SUBSTITUTE — Masters of Text Transformation

Diving into the transformative world of text manipulation, we find two helpful tools: REPLACE and SUBSTITUTE. While both aim to modify the original text, their methods differ. REPLACE focuses in on a specific portion of text based on position, allowing for precise modification. In contrast, SUBSTITUTE scans the entire text string, swapping out every occurrence of a particular substring unless instructed otherwise.

You know the drill, let’s take a look at their syntax before exploring the examples.

REPLACE Function: pinpoints a section of text based on its position and its syntax is:

REPLACE(old_text, start_number, number_characters, new_text)

The original text (i.e. the text you want to replace) is represented by old_text. The start_number denotes where, the position in old_text, you want the replacement to begin, and number_characters signifies the number of characters you would like to replace. Lastly, new_text is what you will be inserting in place of the old characters.

Note: If <number_characters> is blank, or a column that evaluates to blank, <new_text> is inserted at the <start_number> position without replacing any characters.

For more details see:

Excel Online (Business) – Actions

Learn more about: Power Automate Excel Online (Business) Actions

SUBSTITUTE Function: searches for a specific text string within the original text and replaces it with new text and has the following syntax:

SUBSTITUTE(text, old_text, new_text, instance_number)

The main text string where you want the substitution to occur is represented as text, with old_text denoting the existing text string within text that you want to replace. Once the function spots old_text, it replaces it with new_text. If you only wish to change a specific instance of old_text, you can use the optional parameter instance_number to dictate which occurrence to modify. If instance_number is omitted every instance of old_text will be replaced by new_text.

For more details see:

SUBSTITUTE function (DAX) – DAX

Learn more about: SUBSTITUTE

Practical Examples: Text Transformation in Action

Earlier we created a product label consisting of the product abbreviation and the product number. Let’s suppose now we need to create a new label based on this replacing the product number with the color code. We can use the REPLACE function to do this and the expression would look like this:

Product Label Color =

REPLACE (

Products[Product Label],

LEN ( Products[Product Abbrev Dynamic] ) + 1,

LEN ( Products[Product Number Dynamic] ),

Products[Product Color Dynamic]

)

``Here we are creating a new calculated column Product Label Color which aims to replace the product number with the product color code. The old_text is defined as the column Products[Product Label]. Then, remember the syntax, we need to determine the position to start the replacement (start_number) and the number of characters to replace (number_characters). Since both of these are not consistent we use our previous dynamically determined columns to help.

Here is a break down of the details:

- Positioning:

LEN(Products[Product Abbrev Dynamic])+1helps find the starting point which is directly following the product abbreviation. LEN counts the length of theProduct Abbrev Dynamiccolumn value and adds one, this is then used to start the replacement directly after the abbreviation. - Length of Replacement:

LEN(Products[Product Number Dynamic])helps determine the length of the segment we want to replace. It counts how many characters make up the product number, allowing for the product number to vary in length but always be fully replaced.

Lastly, the expression uses the product color code as determined by the Product Color Dynamic column we previously created as the new_text.

The transformation of data can often require several steps of modification to ensure consistency and clarity. We can see in the above the last product code is not consistent with the rest, resulting in a label that is also not consistent. Let’s build upon the previous example using SUBSTITUTE to add some consistency to the new label.

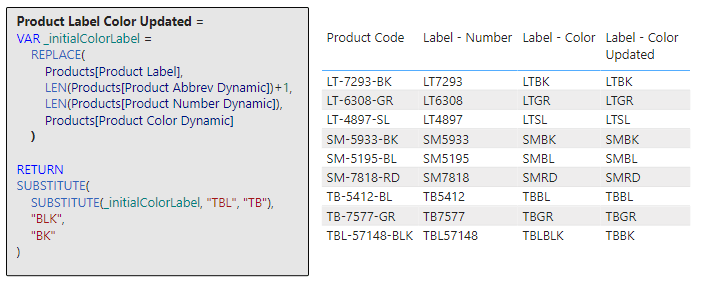

To do this the DAX expression would look like this:

Product Label Color Updated =

VAR _initialColorLabel =

REPLACE(

Products[Product Label],

LEN(Products[Product Abbrev Dynamic])+1,

LEN(Products[Product Number Dynamic]),

Products[Product Color Dynamic]

)

RETURN

SUBSTITUTE(

SUBSTITUTE(_initialColorLabel, "TBL", "TB"),

"BLK",

"BK"

)

Here we start by defining the variable _initialColorLabel using the same expression as the previous example. Then we refine this with a double substitution! The inner SUBSTITUTE (SUBSTITUTE(_initialColorLabel, "TBL", "TB")) takes the initial label as the main text string and searches for TBL and replaces it with TB. The result of this (i.e. TBBLK) is then used as the initial text string for the outer SUBSTITUTE, which searches this string for BLK and replaces it with BK. This produces the new label that is consistent for all products.

Now we are starting to see the true power of DAX Text Functions, this expression does so much more than just a singular adjustment: it first reshapes the product label and then it goes even further to make sure the abbreviation and color codes that make up the label are consistent and concise. It is an illustration of how DAX can incrementally build and refine results for more accurate and streamlined outputs.

Although, these examples are helpful, it may be best to perform these transformations upstream when creating the dynamic extractions. For example the Product Abbrev Dynamic column we created early:

Product Abbrev Dynamic =

LEFT(

Products[Product Code],

FIND("-", Products[Product Code]) - 1

)

Could be updated to :

Product Abbrev Dynamic =

SUBSTITUTE (

LEFT (

Products[Product Code],

FIND ( "-", Products[Product Code] ) - 1

),

"TBL",

"TB"

)

This would ensure consistency where ever the product code is used within the report.

As we continue our journey into the realm of DAX, remember that the right tool hinges on your specific needs. While CONCATENATE and COMBINEVALUES both join text strings, their nuanced differences could significantly influence the effectiveness of your data analysis and the presentation of your data. Choose wisely!

LEN & FORMAT — The Essentials

In the realm of DAX Text Functions, while both LEN and FORMAT serve distinct purposes, they play crucial roles in refining and presenting textual data. Throughout this deep dive into DAX Text Functions, you may have noticed these functions quietly powering several of our previous examples, working diligently behind the scenes.

For instance, in our Product Color Dynamic calculated column LEN was instrumental in determining the appropriate number of characters for the RIGHT function to extract. Similarly, our Yearly Page Title measure makes use of FORMAT, to ensure an aesthetic presentation of the YTD Sales value.

These instances highlight the versatility of LEN and FORMAT, illustrating how they can be combined with other DAX functions to achieve intricate data manipulations and presentation. Let’s take a look at the details of these two essential functions.

LEN Function: provides a straightforward way to understand the length of a text string and the syntax couldn’t be more simple.

LEN(text)

The text string you wish to know the length of is represented by “, just pass this to LEN to determine how many characters make up the string. The text string of interest could also be a column reference.

Note: Spaces count as characters

For more details see:

Learn more about: LEN

Now that you are more familiar with the LEN function revisit the previous examples to see it in action.

Product Color Dynamic =

VAR _firstHyphenPosition =

FIND (

"-",

Products[Product Code]

)

VAR _lastHyphenPosition =

SEARCH (

"-",

Products[Product Code],

_firstHyphenPosition + 1

)

RETURN

RIGHT (

Products[Product Code],

LEN ( Products[Product Code] ) - _lastHyphenPosition

)

Product Label Color =

REPLACE (

Products[Product Label],

LEN ( Products[Product Abbrev Dynamic] ) + 1,

LEN ( Products[Product Number Dynamic] ),

Products[Product Color Dynamic]

)

FORMAT Function: reshapes how data is visually represented, with this function you can transition the format of data types like dates, numbers, or durations into standardized, localized, or customized textual formats. The syntax is as follows:

FORMAT(value, format_string[, locale_name])

Here, value represents the data value or expression that evaluates to a single value you intend to format and could be a number, date, or duration. The format string, format_string, is the formatting template and determines how the value will be presented. For example a format string of 'MMMM dd, yyyy' would present a value of 2023-05-12 as May 12, 2023. The locale_name is optional and allows you to specify a locale, different regions or countries may have varying conventions for presenting numbers, dates, or durations. Examples include en-US, fi-FI, or it-IT.

Note: The result of FORMAT has a text data type, meaning that if a numeric value is formatted using FORMAT it could not then be used on visuals where the values section requires a numeric data type, or it could not be used to perform numerical calculations without converting it back to a number.

Learn more about: FORMAT

Now that you know the details of FORMAT see it put to work by revisiting the Yearly Page Title measure.

Yearly Page Title =

COMBINEVALUES (

" ",

YEAR (TODAY ()),

"- Year to date sales:",

FORMAT ([YTD Sales TOTALYTD], "Currency")

)

In this example, you see that the format_string uses a value of Currency to format the YTD sales. This is an example of a predefined numeric format. For more details on predefined numeric formats, custom numeric formats, custom numeric format characters, predefined date/time formats, and custom date/time formats visit the documentation here:

FORMAT function (DAX) – Predefined Numeric Formats

Learn more about: FORMAT

Beyond Strings: The Culmination of DAX Text Wisdom

Words share our world. And in the realm of data, they offer valuable insights. With DAX Text Functions, you have the power to manipulate, transform, and uncover these insights.

We have explored just a subset of DAX Text Functions during our journey here. There is still more to be uncovered so don’t stop learning here. Keep expanding and perfecting your DAX textual skills by exploring other text functions here:

Learn more about: Text functions

And, remember, anyone who has never made a mistake has never tried anything new. So, don’t be afraid of making mistakes; practice makes perfect. Continuously experiment and explore new DAX functions, and challenge yourself with real-world data scenarios.

Thank you for reading! Stay curious, and until next time, happy learning.

And, remember, as Albert Einstein once said, “Anyone who has never made a mistake has never tried anything new.” So, don’t be afraid of making mistakes, practice makes perfect. Continuously experiment and explore new DAX functions, and challenge yourself with real-world data scenarios.

If this sparked your curiosity, keep that spark alive and check back frequently. Better yet, be sure not to miss a post by subscribing! With each new post comes an opportunity to learn something new.